The Evolutionary Shift in Primate Reproduction

From Twins to Singleton Births: The Story of Ancient Primates

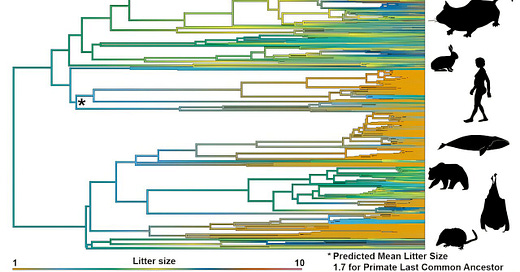

Twins are often celebrated as rare marvels, a quirk of biology that has fascinated humanity for millennia. Many cultures weave twins into myths—twin gods, twin founders of nations, twin symbols of duality in life. But what if twins were not an anomaly, but the evolutionary default? New research is reshaping our understanding of primate reproduction, rev…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Primatology.net to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.