Scratching Through the Mind: What Japanese Macaques Reveal About the Evolution of Emotion

How a Simple Bodily Response Unlocks Complex Cognition in Primates

For centuries, scientists have debated whether emotions begin in the body or the mind. The James-Lange theory, a cornerstone of psychology, suggests that our bodily reactions precede and shape our feelings—we tremble, then feel fear; we cry, then feel sorrow. But while this theory has been tested in humans, what about our primate cousins? Do they, too, experience a connection between their bodily responses and cognitive shifts?

A new study, led by Sakumi Iki and Ikuma Adachi at Kyoto University, explores this question in an unexpected way—through the self-scratching behavior of Japanese macaques. Published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B1, their research suggests that bodily responses can indeed shape cognitive processes in non-human primates. But crucially, the reverse is not true: a pessimistic state of mind does not predict bodily responses.

This discovery offers a fascinating glimpse into the evolutionary origins of human emotion, suggesting that our complex interplay of body and mind may have much deeper roots in our primate lineage than previously thought.

When Scratching Becomes a Window into the Mind

In humans, scratching is often dismissed as a reflex or a response to physical irritation. But in primates, it serves another function—it is a well-documented indicator of emotional distress. From chimpanzees to baboons, increased scratching is often linked to anxiety, frustration, or social tension.

Iki and Adachi capitalized on this link to investigate whether self-scratching in macaques could predict cognitive shifts. To do so, they employed a judgment bias test, a method widely used in animal psychology to measure optimism or pessimism based on responses to ambiguous stimuli.

Their study involved six adult Japanese macaques who were trained to recognize a simple touchscreen task. The monkeys learned that touching a white button led to a reward (a food pellet), while touching a black button led to a mild punishment (a brief delay before the next trial). The real test came when they were presented with a gray button—an ambiguous stimulus that could be interpreted either optimistically or pessimistically.

At the same time, the researchers monitored the macaques’ self-scratching behavior, aiming to determine whether bodily stress responses influenced their decision-making.

Their results were striking:

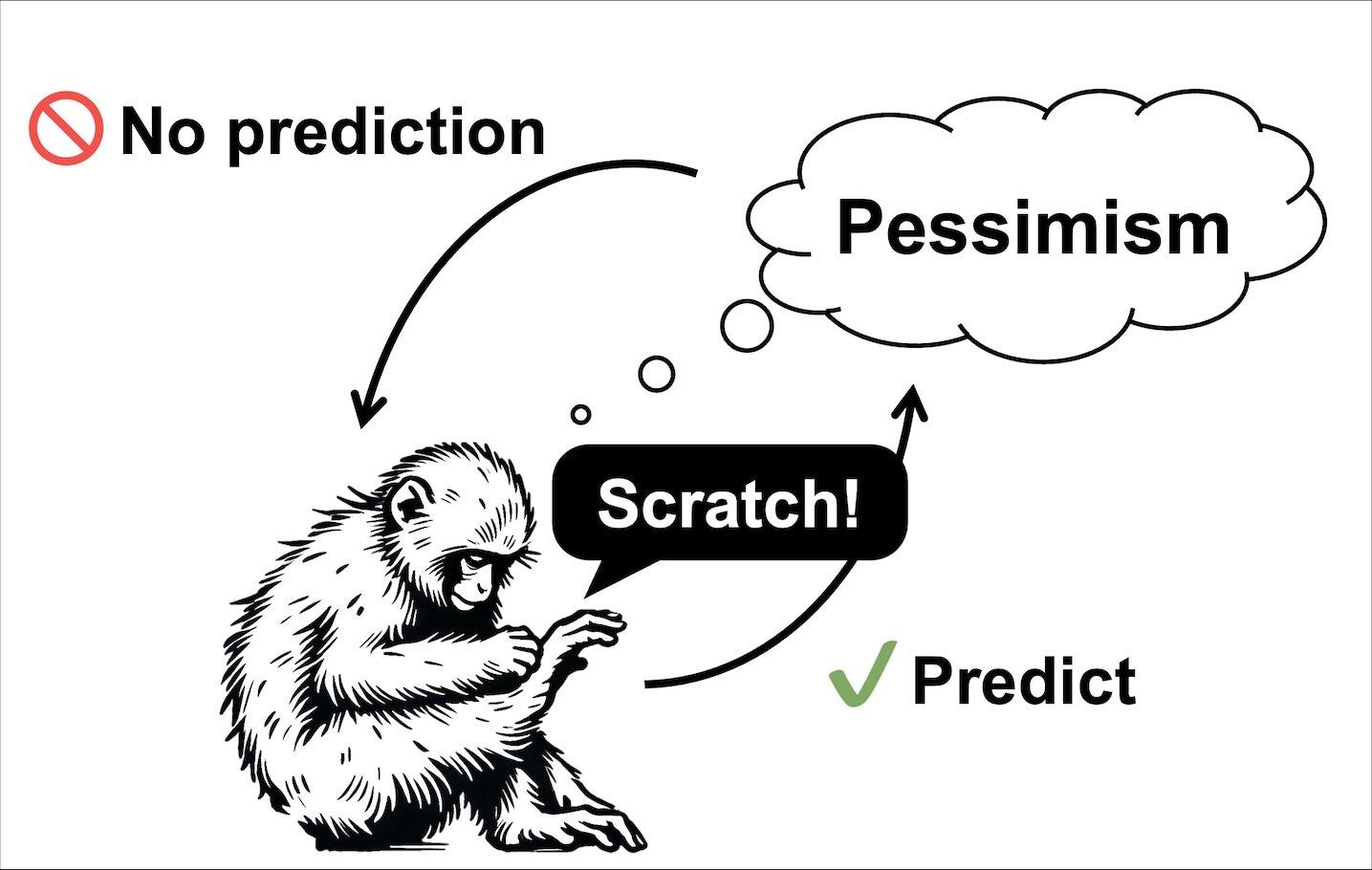

“Our findings support the hypothesis that bodily responses precede and influence changes in cognitive modes, demonstrating that self-scratching predicts subsequent pessimistic judgments, but not vice versa.”

In other words, the monkeys were more likely to interpret the gray button negatively immediately after scratching. But crucially, experiencing a pessimistic moment did not increase their scratching behavior.

A One-Way Street Between Body and Mind?

These findings suggest a crucial asymmetry in the connection between bodily responses and cognitive states in macaques. In humans, the relationship appears to be bidirectional—we cry because we are sad, but crying can also deepen our sadness. In contrast, Japanese macaques exhibit a one-way relationship: their bodily stress responses predict pessimistic decision-making, but not the other way around.

Why might this be the case? One possible explanation is that humans have developed a unique cognitive feedback loop, enhanced by language and introspection, that allows emotions to shape bodily responses in a more complex way. Iki and Adachi speculate that:

“In humans, the relationship between mind and body may have evolved in a distinctive way, influenced by our use of language and advanced introspection.”

For non-human primates, an emotion-first approach may not be evolutionarily advantageous. Instead, responding to immediate bodily signals—such as scratching—before engaging in deeper cognitive processing could offer survival benefits. If a monkey is experiencing stress or discomfort, it makes sense to assume a more cautious, pessimistic stance rather than relying on deeper introspection that could delay decision-making in a dangerous situation.

Evolutionary Implications: Affective Responses in the Wild

This study also has broader implications for how we think about the evolution of emotions in primates. If bodily responses like scratching shape cognitive processing, it suggests that these behaviors may play a fundamental role in decision-making across many species.

In natural settings, this could influence social interactions, risk assessment, and even survival. For example, a macaque that experiences a stressful social encounter may be more cautious in interpreting ambiguous cues afterward—potentially avoiding dangerous situations or aggressive con-specifics.

The findings also raise intriguing questions about other non-human primates. Would similar patterns emerge in more socially complex primates like chimpanzees or bonobos? Would species with different social structures show different patterns of bodily-cognitive interaction?

Future research could expand on these findings by examining a wider range of bodily responses, such as changes in posture, facial expressions, or vocalizations, to determine whether they also predict shifts in cognitive state.

A Thought-Provoking Critique: What This Study Doesn't Tell Us

While Iki and Adachi’s study offers a compelling look at the relationship between bodily responses and cognition, some questions remain unanswered.

First, the study’s sample size was small—only six macaques—which raises concerns about whether the findings are broadly applicable across primates. Additionally, the experimental setting may not fully capture how these processes work in the wild, where macaques navigate far more complex and unpredictable social environments.

Another limitation is the assumption that self-scratching is purely a marker of negative affect. While previous studies support this link, scratching could also serve other functions, such as thermoregulation or social signaling. A more nuanced understanding of scratching across different contexts would strengthen these findings.

Finally, while the study suggests a lack of bi-directionality in macaques, it remains possible that pessimistic cognition affects bodily responses in subtler ways—perhaps through changes in heart rate, muscle tension, or grooming behavior, rather than overt scratching.

Despite these limitations, this study marks an important step toward understanding the deep evolutionary roots of emotion and cognition.

What Scratching Can Teach Us About Ourselves

Iki and Adachi’s research reveals that in Japanese macaques, bodily responses drive cognitive shifts, not the other way around. This finding challenges long-held assumptions about the mind-body connection and suggests that fundamental aspects of emotional processing may be evolutionarily conserved across primates.

For anthropologists and primatologists, this study opens new avenues for exploring how affective states shape behavior in non-human animals. It also raises important questions about how human cognition evolved to incorporate a more complex, bidirectional relationship between body and mind.

As researchers continue to explore these questions, one thing is clear: sometimes, the simplest behaviors—like a scratch—can offer profound insights into the origins of emotion, cognition, and what it means to be primate.

Related Research

For those interested in exploring further, here are some relevant studies:

Cognitive Bias in Animals

Paul ES, Harding EJ, Mendl M. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005. DOI: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.01.002Emotional Contagion in Primates

Palagi E, Norscia I, Demuru E. PeerJ. 2014. DOI: 10.7717/peerj.519The Evolution of Emotion Across Species

Anderson DJ, Adolphs R. Cell. 2014. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.003

Iki, S., & Adachi, I. (2025). Affective bodily responses in monkeys predict subsequent pessimism, but not vice versa. Proceedings. Biological Sciences, 292(2040). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2024.2549